As the Labour party continues to decay under the shambling non-leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, its MPs find themselves freer to pursue their own interests. One of them, Gerald Kaufman, has decided to campaign against split infinitives.

Today he told the House of Commons his view of the government’s new White Paper on education:

One of the most morale-destroying assignments that I have had in this House has been to read this White Paper. It is riddled with jargon, with ungrammatical structures and with split infinitives.

So I had a look.

The White Paper is indeed an unlovely read, with plenty of official jargon. But split infinitives? I found two in the first chapter. Here’s one:

It will also help us to better support schools to develop a strong and diverse pipeline of great school and system leaders

Hardly prose to inspire. But the split infinitive – “to better support” – is fine. In fact, it’s better than fine: it’s essential.

Where else could the adverb “better” go? There are four options and they’re all terrible:

- It will also help us better to support schools to develop a strong and diverse pipeline of great school and system leaders

- It will also help us to support better schools to develop a strong and diverse pipeline of great school and system leaders

- It will also help us to support schools better to develop a strong and diverse pipeline of great school and system leaders

- It will also help us to support schools to develop a strong and diverse pipeline of great school and system leaders better

Option 1 is confusing: the adverb is right between two verb phrases, leaving unclear which it applies to: is it the helping or the supporting that will be done better?

Option 2 is much worse: it’s positively misleading. In theory it’s ambiguous: “better” could apply to the support or the schools. But in practice the natural reading is the schools.

Option 3 has the same problem as 1: will the supporting or the developing be better?

Option 4 is triply ambiguous: “better” could mean the helping, the supporting or the developing. The likeliest guess would be to give it to the nearest verb: “develop”.

There is a fifth option, which would be to cut the “to”:

- It will also help us better support schools to develop a strong and diverse pipeline of great school and system leaders

This is the best of the five: the only way to interpret it is the right one. But there’s a risk of a miscue. As in option 1, “better” follows right on from “help us”, so it could easily at first be taken to apply to that. After a couple more words things become clearer, but the reader’s brain has to do a quick gear change to adapt.

Also, if you’re worried about split infinitives, you should note that option 5 doesn’t so much split one as tear it apart and throw half of it away.

But you shouldn’t be worried about split infinitives. Not because we live in a liberal era in which “anything goes”, but because split infinitives (like the White Paper’s one) are useful. By tucking a word like “better” snugly inside the infinitive, you make crystal clear what it applies to. The split makes the grammar and thus the meaning of the sentence clearer.

As I’ve documented at great length, split infinitives are a centuries-old feature of English whose opponents, dating back only to the Victorian age, have never been able to muster a coherent case.

But these opponents, by talking as if they guard an eternal but fragile truth rather than a baseless and unhelpful superstition, have intimidated many people into thinking they must be right.

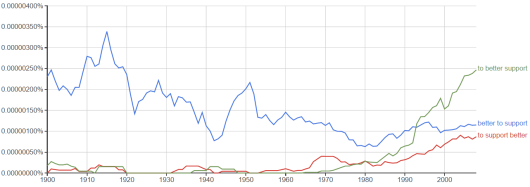

Luckily, their hold is weakening. Look at how often the phrases “better to support”, “to support better” and “to better support” have been used in books – published, edited books – over the last century:

Split infinitives come naturally to most people. They are good, clear, grammatical standard English. And no one can take them away from us.

Comments

So according to Kaufman, split infinitives are not an “ungrammatical structure”, but a separate category of badness?

I’m a copy editor with around 40 years of experience and usually work for academic presses – and I couldn’t agree with you more!

Maybe (I have no idea) he wasn’t referring to that particular split infinitive…..?

It is a bit misleading to talk of ‘tucking a word like “better” snugly inside the infinitive’. This suggests that ‘to’ is part of the infinitive. It often accompanies the infinitive, but it is no more part of the infiinitive than ‘will’ is part of the verb in ‘We will eat’. This is shown not only by the fact that ‘to’ can be separated from the associated verb in ‘split infinitived’ but also by the fact that it can apear on its own in cases of ellipsis, e.g. ‘They told me to leave but Im not going to’..

In terms of linguistic terminology, you’re right, but I’m going with common parlance, in which an “infinitive” is “to + [verb]”.

Someone (I forget who) came up with a lovely analogy of the “to” being the infinitive’s butler: sometimes the butler works on behalf of the infinitive (as in your eg), sometimes they’re together, sometimes both appear but separated, and sometimes the infinitive leaves its butler at home.

The not splitting of the infinitive is an ancient argument from a long-dead tongue. Basically, you can’t split the infinitive in Latin because it is one word. Therefore, self proclaimed language purists think we shouldn’t do it in English. Well, if the English language is going to increasingly develop as a mode for modern communication, we must ignore age-old, limiting ideals (did you see what I did there?) Get splitting writers!

Trackbacks

[…] More in split infinitives: https://stroppyeditor.wordpress.com/2016/04/13/use-split-infinitives-to-better-support-your-meaning/ […]