A recent study, as you may or may not have heard, has found that teaching grammar to Year 2 children (age 6-7) does not improve their writing. But that’s not what it found.

The study, by researchers at UCL and the University of York, did not compare grammar teaching with no grammar teaching. It compared one particular programme of grammar teaching, called Englicious, with the grammar teaching that schools were doing already, and it found that Englicious produced results that were essentially no better than the other grammar teaching.

The research paper makes this very clear, although the conclusions section seems to stray a little into over-generalisation. And the news articles published by the two universities both lead with the generalised claim:

The teaching of grammar in primary schools in England (a key feature of England’s national curriculum) does not appear to help children’s narrative writing, although it may help them generate sentences, according to new UCL-led research.

UCL

Lessons on grammar are a key feature of the national curriculum taught in England’s primary schools, but they don’t appear to help children to learn to write, new research reveals.

York

This is the angle the media coverage has largely followed. (Note to journalists: always read the PDF.)

The background

Grammar teaching, which has become a bigger part of England’s national curriculum since 2014, is contentious. Some see it as providing the essential building blocks of literacy and good communication, while others think it a bewildering morass of jargon that has little relevance to how people really speak and write.

I broadly support grammar teaching in principle, although I don’t have strong views on how much to teach at particular ages and I can’t claim any expertise on teaching methods. But I have liked the idea of Englicious since I first heard about it.

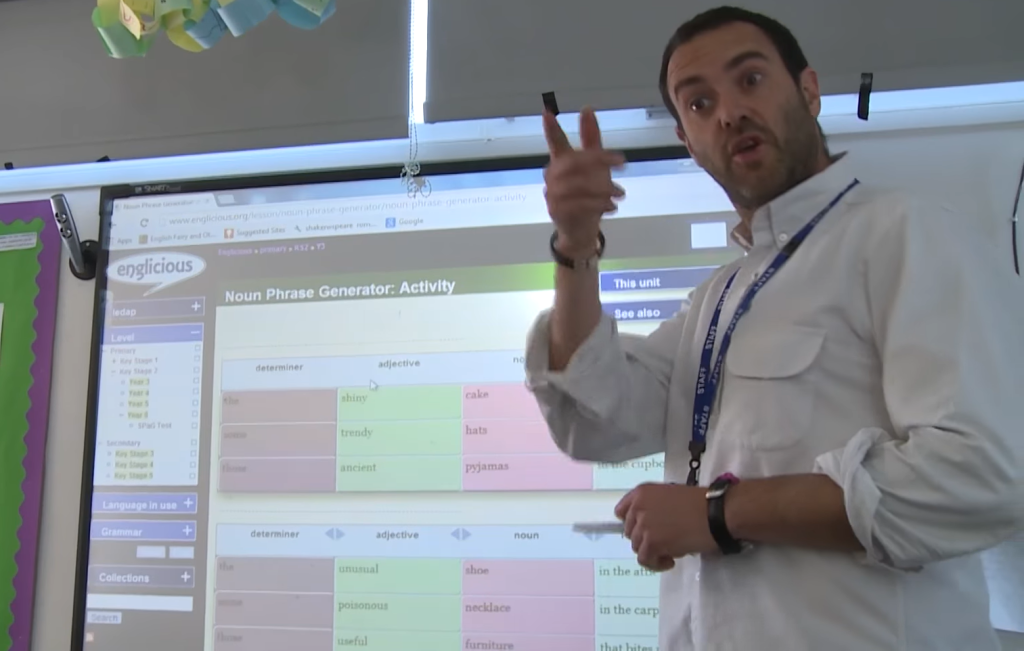

Englicious is a set of resources to help teachers run classes on grammar in line with the curriculum. It aims to address two of the big worries about grammar teaching: that it’s dull and off-putting, and that the theoretical knowledge of grammar is disconnected from children’s actual writing skills. Its approach is strong on interactive exercises, trying to incorporate some fun, and it links grammatical concepts with practical writing work. This sounds to me like a great idea.

The study

To test it, the researchers recruited primary-school teachers and put them into two groups: one group used Englicious with their Year 2 classes, after an introduction to the resources and training in how to use them; and the control group taught grammar using the various approaches they were already using (this is the crucial detail that most of the coverage has obscured).

The research paper highlights one distinctive feature of the Englicious approach:

One key difference between intervention and control schools… was that the Englicious lessons consistently included an opportunity for pupils to apply their learning through an independent writing activity that was part of the Englicious lesson. It appeared that this was not a typical approach in every lesson observed in the control schools. In the control schools a wide range of teaching strategies was seen being used to support learning about grammar, for example general approaches to grammar teaching that included using a text to contextualise teaching of grammatical terms and their properties; teacher-led strategies including deliberate inclusion of errors when presenting texts; whole-class activities including discussions while pupils were sitting on the carpet; and use of mini whiteboards for pupils to write sentences…

Because Englicious was designed to link grammar to writing, the main way the researchers assessed its effect was through a narrative writing test, in which pupils had to create a narrative based on a prompt. They also used a sentence generation test, in which pupils were given two words as a prompt and had to generate sentences using them both – a task more focused on grammatical understanding.

The findings

Looking at the test scores from before and after a ten-week period of teaching, the study found that Englicious had no effect on the pupils’ narrative writing scores relative to the control group, and that it may possibly have improved sentence generation scores a little, but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.25).

The researchers gamely describe the second finding as “encouraging”, although I think “disappointing” would be a fairer assessment. Englicious may have been slightly helpful with actual grammar teaching (more research is needed), but it failed in its primary objective.

This doesn’t mean the approach is worthless: it seems to be at least as good as other current methods; it may have other benefits that weren’t covered by the two tests; and it might help pupils’ learning to last for longer than this ten-week study. And the teachers who used Englicious gave largely positive feedback on it in questionnaires, saying that the lessons were a positive experience for both them and their pupils. That counts for something. They also made some suggestions that could improve Englicious.

The confusion

But there’s no escaping the fact that the study didn’t find the main desired effect. And here, perhaps, is where the widespread misunderstanding of the findings was born. The paper says:

The lack of effect on narrative writing is the main outcome of our research, and is consistent with previously published studies on grammar and writing at primary education level.

These older studies, though, didn’t look at Englicious or the post-2014 English curriculum. The general thrust of the previous research, as this paper summarises it, is that grammar teaching, on the whole, shows little if any sign of improving pupils’ writing. To further support that conclusion, you would have to compare grammar teaching (of some kind) with no grammar teaching, not compare different kinds of grammar teaching.

One sentence on the paper’s methodology acknowledges this problem:

The context of England’s national curriculum requirements meant that it was not feasible to have a control group that did not have any grammar teaching, a control that some would regard as a better comparison.

That last bit seems quite an understatement.

In light of this problem, I struggle to see how the following conclusion is a fair reflection of a study that compared different methods of teaching grammar:

The research found that seven-year-old pupils’ narrative writing was not improved as a result of grammar teaching.

I suppose the researchers could say “We gave it a really good shot, but all we’ve got is another way that doesn’t work; this suggests that the whole idea of connecting writing skills to grammar teaching is doomed to failure.” But it’s clear that they think the Englicious approach has room for improvement.

The upshot

I wish the Englicious team the best in further developing their work. Their approach has merit – it’s just not yet clear how much. And I agree that there are broad grounds for concern about how grammar teaching can improve writing skills.

This was a valuable and well-conducted study – the first randomised controlled trial in the world to examine this topic. But I think it has been over-interpreted: in parts of the conclusion and the university press releases, and in media reports that don’t look too closely at the detail.

Grammar teaching is politically fraught. For many people, it taps into notions of authority, discipline and tradition versus liberalism, diversity and modernity. Debates on it can get pretty heated, with people often falling back on ideological preconceptions. So if we want to improve how grammar is taught, we all need to be clear about what the relevant evidence does and doesn’t show.

Comments

Knowing your grammar hasn’t damaged your writing skills!

Hope you noticed that you made it into Language Log this week! https://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=53967

Reblogged this on GRAMMARIANISM.

I enjoyed this piece. Hope you can add ‘Grammarianism’ to your blogroll!

Trackbacks

[…] The post on Stroppy Editor is at https://stroppyeditor.wordpress.com/2022/03/14/writing-skills-and-grammar-teaching-the-misinterprete… […]